About models and modellers (Part 1):

What is it about models?

The now long vanished model shop in London, Under Two Flags, used to have up a sly little sign on its wall that read: “The difference between men and boys is the price of their toys”.

You could take that literally to mean that an adult can spend more on a hobby than he did as a child . . . and that’s often the reason he does.

You could take that literally to mean that an adult can spend more on a hobby than he did as a child . . . and that’s often the reason he does.

But it might also have the wider meaning – that the designer clothes, gadgets and consumer items we hanker after are all just grown-up versions of our childish passions.

Except, of course, it’s more acceptable in adult company to lust after a Gucci key ring than a hunk of resin. To the non-geek world, the modelling geek’s desires are incomprehensible and slightly suspect. The non-geek refuses to differentiate between ‘toys’ and ‘models’; any more than he would between ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’.

And it’s useless to explain.

It is always and absolutely pointless to explain anything because the only fixed and immutable law that applies in these circumstances is this one: you either get it or you don’t.

You don’t get my interest because you’re not a modeller.

You are a modeller but your total obsession with Gerry Anderson leaves me completely cold, whilst my driving compulsion to own every Takayuki Takeya model kit ever produced fills you with an equal indifference.

It’s a weird world.

To paraphrase the great seer Stephen King: “Strange are the things at which a man warms his heart”.

Nevertheless, I have been thinking about this subject lately . . .

Why do people like models? Why are certain people drawn to certain subjects? I thought I might find a few answers to those questions by looking at what lies at the heart of the hobby and also by tracing my own involvement. Like most of us, I know what I like but I haven’t really stopped to think why I like it . . .

Firstly – what’s interesting from any perspective is that so many people are turned on by small things. Miniature versions of anything get us going – people, animals, cars, buildings, you name it. Let’s call this the bonsai impulse because the Japanese are probably one of its finest exponents.

A psychologist would probably argue that we like physical models of things – though we often call them by other names: figurines, sculptures, netsuke – because we construct mental models of the world all the time.

That’s a fundamental part of the way we operate as human beings: by building versions of the environment we live in inside our heads. It is the containment and coherency of a model that appeals to us although we may not be aware of the reason.

“The first forty years of childhood are the hardest . . .”

A psychiatrist, on the other hand, would undoubtedly claim that it’s all about the power of association. A child’s toy represents an emotional bond; it also gives the child power by shrinking the world down to scale. The attraction of models is therefore essentially regressive, a wish to recreate the comforting experiences of childhood.

This perspective is backed to some extent by the evidence: the kind of subjects that are popular in the figure modelling world either have a heavy bias towards nostalgia (old films, old tv shows, old comic heroes) or an association with past glories and exploits; military figures being a prime example.

An important difference between a toy and a model is the need to go through the process of construction.

The difference is crucial and it’s one reason that hard-core modellers are so sniffy about so-called pre-paints; the ready painted statuettes that seem to be taking over model shops. Despite the quality of these, which has improved considerably recently, they don’t offer anything like the creative satisfaction of a model kit.

The pleasure a genuine modeller gains from a model is owning something uniquely stamped with his own personality; a product of his own skills and artistic ability. Without these attributes, you’re a mere collector who might as well be collecting china thimbles or beer-coasters.

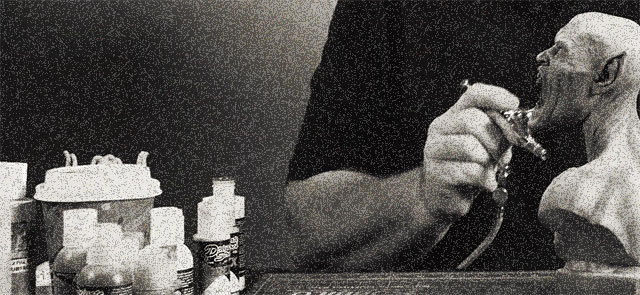

Art is not too fancy a word to use in this context. See the work of a master painter, the intricacy of the work, the painstaking detail, or see a sculpture done by one of the truly talented model sculptors, and you cant help but be impressed. Make a half decent job of assembling and painting a model yourself and you have a reason to feel proud.

None of the above really explains though why a bunch of grown men (it’s usually men) are drawn irresistibly to spending their time, and often quantities of their hard earned cash, building and painting little artefacts to clutter up their shelves.

Well, I can’t speak for you, brothers (and the sister at the back), but here is my own sad story . . .

David Clough© 2004

Afterthought

This article is about what attracts people to modelling but it doesn’t explain why I’m personally drawn to it or to certain subjects particularly. On the front page of this site I assert that, unlike many kit-builders, I don’t seek out kits based on movie characters, and that’s generally true; but the reason I do like one type of kit and not another are a little more complex than that.

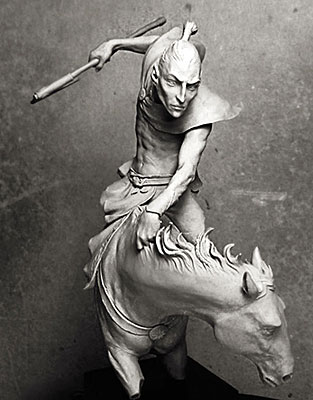

Firstly it’s the quality of the sculpting. Even subjects that I’m not normally attracted to – military, say – can appeal to me if they are exceptionally sculpted. I don’t usually give in to such impulses because life is too short (and I have too many unbuilt kits) but I can still admire the work that goes into them.

Firstly it’s the quality of the sculpting. Even subjects that I’m not normally attracted to – military, say – can appeal to me if they are exceptionally sculpted. I don’t usually give in to such impulses because life is too short (and I have too many unbuilt kits) but I can still admire the work that goes into them.

Good sculpting has a dynamism that is most recognisable when it’s not present. Then the figures seem stiff and doll-like. That dynamic quality is what brings sculpting to life, the feeling that the figure has stopped in the middle of something.

Every figure is potentially part of a tableau, even a bust, which means that every figure potentially tells a story. As a writer that something that interests me very much and the subjects that interest me most have a romantic, mysterious or gothic feel to them.

The reason that I’m not drawn to movie based figures is precisely because the romance is missing. The story has been told already, more effectively, on screen and the figure is just a souvenir of that experience. Of course, if I don’t know the films or haven’t seen them, as is the case with some of the Japanese models I own, then it’s not spoiled for me. Similarly, there are some sculptures which are so intrinsically well done that you can forget or forgive they are representations of something else.

David Clough© 2017